Aren’t we all so lucky that Van Gogh failed his theology exams and decided to become an artist. Our art galleries, our front rooms, our greetings cards, our phone cases, would be all the poorer had he passed.

Vincent in Paris

We are also all very lucky that in 1886, Van Gogh decided to go to Paris. It was in Paris that he discovered colour, and became the artist that we know and love. Before 1886, his paintings are dense and muddy-brown, deeply influenced by the Dutch artistic tradition that centred simple scenes of peasant life. The Potato Eaters epitomises this early period - a painting where the only hint of colour comes from a thin glimmer of lamplight. It’s hard to believe that in only three years, this artist would be producing landscape paintings so blazingly vivid that you need SPF to stand in front of them.

Paris in the 1880s was a hotbed of creativity, with Impressionism (which had enjoyed a heyday in the 1870s) disintegrating into a myriad of different ‘isms’ - Symbolism, Synthetism, Pointillism, each one with its own cast of eccentric characters and bold claims to artistic truth. When he moved to the city, he must have felt like a child in a toy-shop.

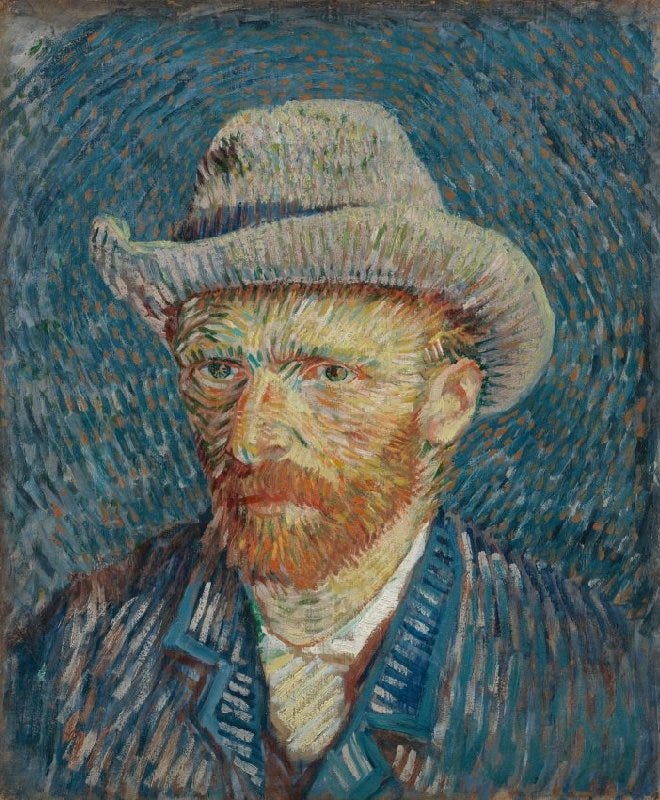

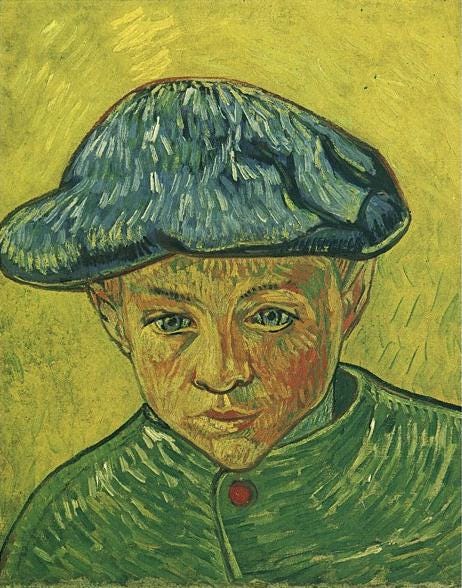

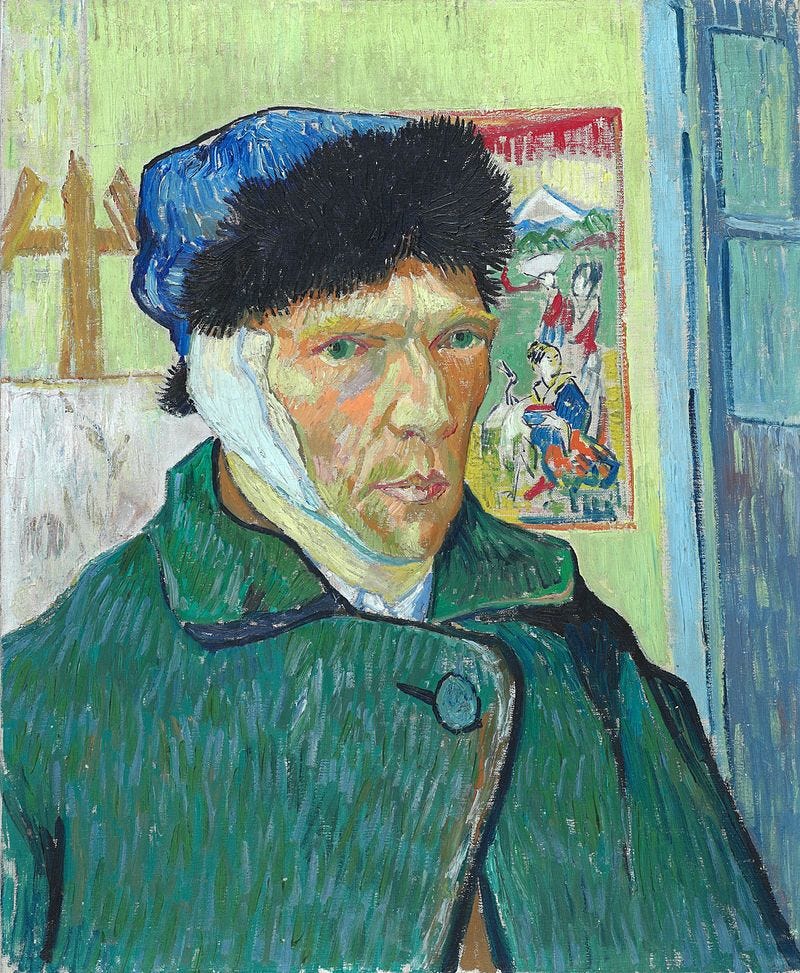

Just look at these two self-portraits: the first painted when he was relatively new to the city, the second just before he departed for the sunnier climes of the south of France. It’s like someone has switched on a light.

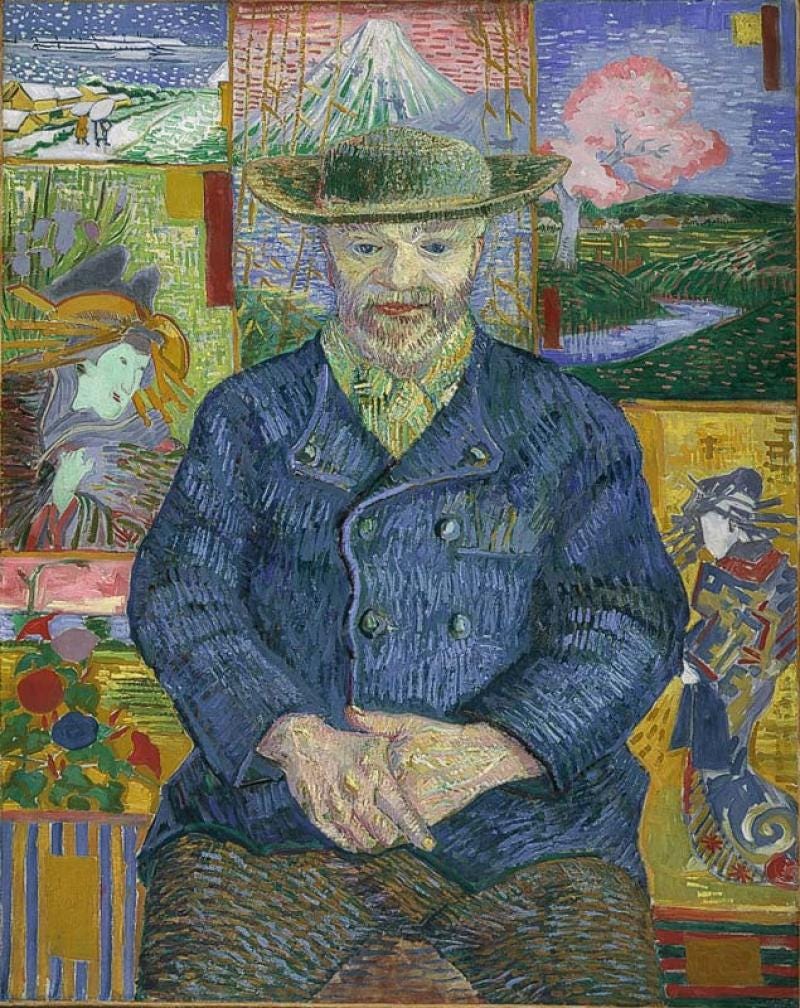

Van Gogh had loved Japanese Ukiyo-e prints before coming to Paris, but it was in Paris that he became fully immersed in their visual world. Ukiyo-e literally means ‘pictures of the floating world’: these were cheap, diverting images of the actors, prostitutes, beauties and folk heroes that populated the theatre and red-light districts of Japanese cities in the Edo period. These prints were in many ways the opposite of conventional Western art: instead of meticulously calculated linear perspective, edges were cropped and visual frameworks distorted, instead of subtle tonal modelling, outlines were bold, and colour was blocked.

Van Gogh’s collection soon numbered hundreds, and in 1887 he put on an exhibition of then at the Café du Tambourin in Montmartre. He made many copies of the prints, and painted his friend and supporter the art-dealer Julien Tanguy with them spread out behind him like a banner of victory, the coming of a new age of art.

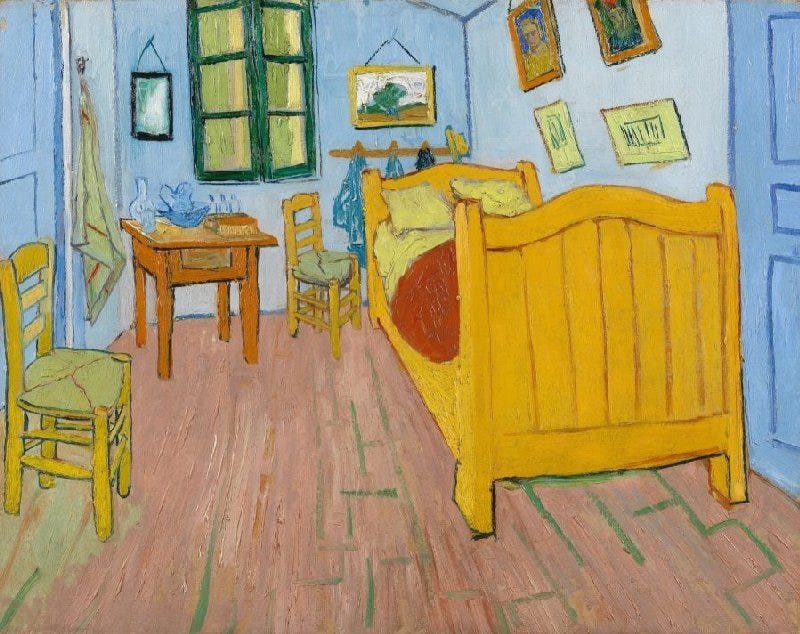

We see the influence of these Japanese prints all over Van Gogh’s later paintings: the pure colours, the bold contours, the radical way of conceiving pictorial space. The Bedroom, with its sloping floor, clean lines, fresh, vivid colour is painted in the spirit of this images, and its subject matter - a poor man’s bedroom - depicts the same humble, everyday subjects as the prints portraying tea houses and brothels.

Van Gogh also encountered Pointillism in Paris. This ‘ism’ is characterised by the ‘dot’ technique: applying dabs of paint whose colours simultaneously juxtapose and merge in a process known as ‘optical blending’. It’s a bit like how pixels work: tiny dots of colour being blended by the brain of the viewer to form a coherent image. The Pointillists rejected form in favour of colour (in Western art history, these are the Big Two: also known as disegno and colore, the dispute over ‘which is better’ goes back to the Renaissance). We can see this technique at play in some of Van Gogh’s later paintings such as Flowering Garden and Sower at Sunset.

After two years of rigorous experimentation in Paris, Van Gogh moved to the Provençal town of Arles, where he lived from February 1888 until May 1889. The 187 sun-drenched paintings which he produced there can be thought of as the immediate, radical effects of Paris.

Colour and Emotion

If you read through Van Gogh’s letters (mostly written to his long-suffering brother Theo), you quickly realise that colour was far more than a descriptive tool: it was a deeply emotive, symbolic force.

Describing his painting of the Night Cafe, he wrote, “I’ve tried to express the terrible human passions with the red and the green.” In a letter written the following day, he writes that, through the use of colour, he had “tried to express the idea that the café is a place where one can destroy oneself, go mad or commit a crime… to express the powers of darkness in a common tavern.”

We tend to associate Van Gogh with the colour yellow: the wheat fields, the fiery yellow stars, the sunflowers. He was obsessed with yellow: the house he shared with his fellow-artist Gauguin was even called ‘the Yellow House’, its walls painted a buttery citrus.

The famous sunflowers were painted in anticipation of Gauguin’s arrival and the yellow speaks of his hope and excitement for the possibility of a ‘Studio of the South’ an ‘artists’ cooperative’ in the style, he believed, of Japanese artistic communities. The artists would work together to create ‘the art of the future’, a balm to modern human society, an alternative to religion.

In a letter to Theo from the time he was painting the Sunflowers, Van Gogh wrote

“Sunshine, a light which, for want of a better word I can only call yellow — pale sulphur yellow, pale lemon, gold. How beautiful yellow is! …Ah, I’m always wishing that the day will come when you’ll see and feel the sun of the south.”

Van Gogh may have had synathesthia: when a response to stimuli linked to one sense is also produced by another. People with synaesthesia may hear colours, taste words, or associate different personalities with different shapes (I actually have it very mildly - for me, days of the week and months of the year all have specific colours and places in a visual chart; I can’t think of ‘Monday’ without visualising it. It wasn’t until I was a teenager that I realised that not everyone had this!).

We read in his letters that Van Gogh associated particular colours with specific personalities. In August 1888, for example, he wrote that he would like to paint a portrait of “an artist friend who dreams great dreams” and that the portrait will express “the love that I have for him” through “the shining fair head against the rich blue background.” This imagined painting was realised in the portrait of the artist Eugene Boch. The warmth of the “orange, chrome, pale yellow” against the “richest, most intense blue that I can contrive” is a visual manifestation of Boch’s friendship with Van Gogh and mystery as a creative individual.

A labour of love

Despite the radical change that his time in Paris brought to Van Gogh’s painting, there are continual threads that run throughout his artistic life, unbroken by his move to and from an exciting modern city. One of these threads is a love for the Realist painter Jean-Francois Millet, referred to almost religiously by Van Gogh as ‘father Millet’. Millet’s earthy paintings of peasant workers going about their daily life in the French countryside have a deep spiritual quality to them, with each solid, simply dressed figure treated with a deep dignity, even reverence. In his Man with a Hoe, the labourer’s stocky body, exhausted from a day of honest work, has the gravitas of a hero after a battle.

The dignity of a hand-to-mouth, humble existence is exemplified by Van Gogh in his pre-Paris paintings, such as the Potato Eaters, but we also find a deep respect for honest work throughout his Arles oeuvre. His portraits of the Roulin family, particularly the patriarch Joseph Roulin, have this combination of down-to-earth respectability and stoic heroism. Joseph fills the humble wooden chair like a king on a throne, and his crown is his postmaster’s hat, the word postes emblazoned in bold gold lettering.

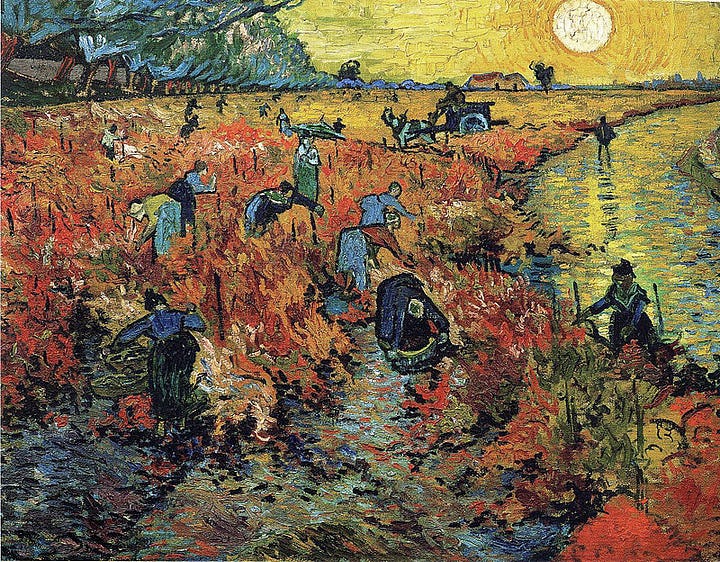

Millet’s veneration for the dignity of physical labour is also apparent in many of Van Gogh’s landscapes, which are often peopled with toiling agricultural labourers. The difference between these Arles landscapes and his early, pre-Paris work is mostly the weather: gone is the drizzly grey, replaced with a burning yellow sun. The Red Vineyard, depicting the grape harvest, is very similar to his early paintings of potato farmers if you were to apply a black-and-white filter. He never abandoned his original mission to become a ‘painter of peasant life’.

I love the art critic John Berger’s take on Van Gogh’s reverence for physical labour. Berger described Van Gogh’s obsession with work as a motif as linked to his whole attitude to art-making and creativity:

“One also knows from his letters that nothing appeared more sacred to Van Gogh than work. He saw the physical reality of labour as being, simultaneously, a necessity, an injustice, and the essence of humanity throughout history. The artist’s creative act was for him only one among many such acts. He believed that reality could best be approached through work, precisely because reality itself was a form of production… His paintings imitate the active existence - the labour of being - of what they depict.”

Van Gogh became fixated on one particular motif used by Millet: the Sower. This image of a solitary figure striding across a loamy field, rendering it fertile with handfuls of seeds, was returned to again and again by Van Gogh in his art and in his letters. He wanted to ‘translate’ the “colourless grey” of Millet’s original image into his own ‘language of colour’. He wrote: “Can we now paint the sower with colour, with simultaneous contrast between yellow and purple for example?... Yes — definitely.”

Art and Religion

Van Gogh had been a zealously religious man, with many of his early letters reading like sermons, but began to become disillusioned around 1881 when he fell out with his Protestant pastor father. When he lost his faith, he transferred many of his religious ideas into his art. He came to understand art as a modern alternative to religion, providing the solace which in the past, people had sought from the church. This idea was the crucial reason why he was so determined to set up an artists’ cooperative: to create this ‘art of the future’, alongside Gauguin and the others artists he hoped would join them.

One of the most important religious ideas that permeated his Arles paintings is the concept of infinity, or eternity, understood in terms of regeneration and renewal, and often associated with intense physical labour. These ideas can be traced back to his early, fanatically religious letters. In 1876, for example, he wrote:

“The old eternal faith and love of Christ, it may sleep in us but it is not dead and God can revive it in us. But though to be born again to eternal life, to the life of Faith, Hope and Charity – and to an evergreen life – to the life of a Christian and of a Christian workman be a gift of God… yet let us put the hand to the plough on the field of our heart…”

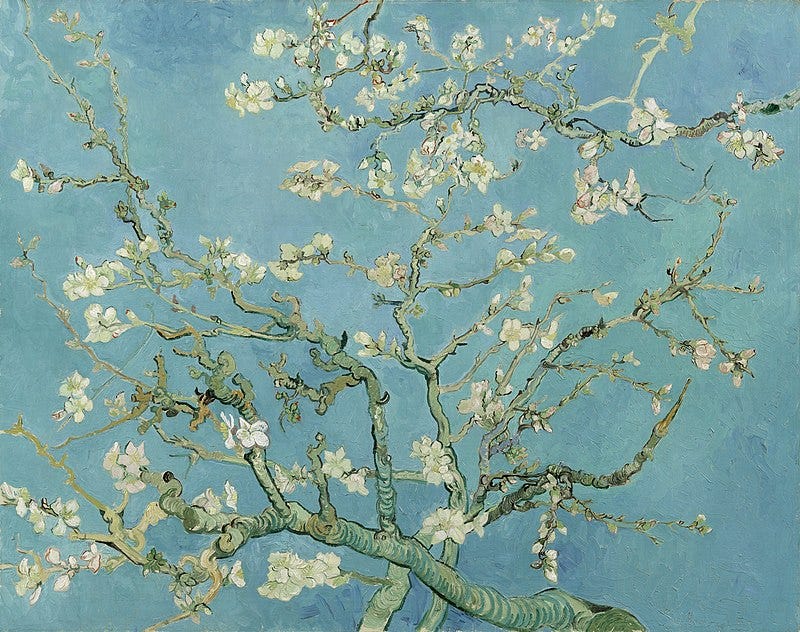

Despite Millet’s enduring influence on Van Gogh’s artistic vision, there is a key difference in how they approached the heroism of labour. Millet’s workers are oppressed by the harshness of their work, whereas Van Gogh’s workers are radiantly optimistic, at one with the landscape, and bursting with energy. They are agents in this spiritual process of regeneration. The image of Millet’s Sower captivated him because of its links to Jesus’ Parable of the Sower, described in his letters as “an exemplar of the Biblical labourer”. The Sower who plants his seeds on fertile ground came not to represent the Gospel, but a new art for the future, and a spiritual ideal of creative generation and re-generation. He wrote to fellow artist Emile Bernard that he had “a hankering after the eternal of which the sower and the sheaf of corn are the symbols”.

It is not insignificant that the majority of the sunflowers he painted are not flowers in full bloom, but rather seedheads.

Arguably, all of Van Gogh’s Arles nature paintings are influenced by these ideas. His paintings of blossoming trees, fields of wheat, harvests and the autumn leaves emphasise the changing and regenerative power of the seasons, and of nature as a source of the infinite – an alternative to God, or perhaps just another way of seeing him. Similarly, in his portraits of the Roulins, Van Gogh sought to “paint men or women with the touch of the eternal, whose symbol was once the halo, and which we try to convey by the very radiance and vibrancy of our colouring”.

Mental illness

It is pretty much impossible to talk about Van Gogh without a mention of his mental illness. Art historians and psychologists have puzzled over what his ‘madness’ may have been (that resulted in the infamous ear-cutting incident) with suggestions ranging from epilepsy, borderline personality disorder, schizophrenia and alcoholism.

I think it is unhelpful to devote too much energy to finding the right 21st-century medical label to attach to a historical figure, mostly because I think it tempts us to think that such a label ‘explains’ their life. Whatever Van Gogh’s illness was, it does not offer a neat, scientific ‘explanation’ to his art, nor should it seduce us with a heroic image of a tormented creative that stereotypes the complexity of his life and work.

A sensitive and considered examination of Van Gogh’s mental illness can be found in Martin Gayford’s brilliant book the Yellow House. Gayford suggests that Van Gogh had bipolar disorder, which allowed him to see the world “with rare intensity”. This is because bipolar disorder is characterised byterrible periods of depression and contrasting periods of ‘mania’, filled with creativity, huge ambition and indefatigable energy. It is difficult to ascertain what Van Gogh’s art would have been like without this mental illness. It may be that his work would never have reached such heights of colourific intensity.

Gayford’s persuasive argument is one of Van Gogh’s defining characteristics as a creative was his ability to make connections between ideas and symbols - such as the Biblical image of the Sower, and the idea of the ‘art of the future’, and an image of sunflowers in a vase. Gayford’s analysis of Van Gogh cutting off his ear lobe in a fit of madness convincingly suggests that it was making intense connections between different ideas that led him to commit this very specific act of self-harm. (To summarise, it was a connection between Simon Peter cutting off the ear of High Priest’s servant as Christ was arrested, a reference to ear-cutting in Zola’s The Sin of Father Moulet, and newspaper reports of Jack the Ripper).

It is evident that the numerous influences on Van Gogh were not only wide-ranging and varied, but also synthesised in complex ways. It was perhaps Van Gogh’s mental illness that enabled him to link and synthesise the various different influences acting upon him - from Japanese prints, Biblical parables, Realist paintings of peasants, and the sensory resonances of particular colours.

It’s easy to get a bit snobbish when you see an artist’s work replicated constantly, and often pastiched, but I resist it when it comes to Van Gogh, because it is an inevitable outcome of the sheer universal appeal of his art – and I think that is wonderful. Better to be universally loved than the preserve of some exclusive art-world elite. I do think it is sad, however, that he has come to represent a kind of stand-alone genius figure, a lonely, tormented soul whose art emerged from a magical Inner Creative Force. This divorces him not only from a rich and textured artistic context that he was deeply engaged with, but from his own creative experimentation. I want to end this little exploration of Van Gogh’s artistic influences with an excerpt from John Berger’s Portraits, because it summarises so beautifully the reason why his paintings remain so magnetic, and so difficult to draw your eyes away from.

“He was compelled to go even closer, to approach and approach and approach. In extremis he approaches so close that the stars in the night sky become maelstroms of light, the cypress trees ganglions of living wood responding to the energy of wind and sun. There are canvases where reality dissolves him, the painter. But in hundreds of others he takes the spectator as close as any man can, while remaining intact, to that permanent process by which reality is being produced.”

All images unless otherwise credited taken from Wikipedia or from the Van Gogh Museum https://www.vangoghmuseum.nl/en/collection

Recommended Reading:

Martin Gayford, The Yellow House: Van Gogh, Gauguin and Nine Turbulent Weeks in Arles (2006)

John Berger, ‘Vincent Van Gogh (1853 - 90)’ in Portraits, ed. Tom Overton (2015)

Ingo F. Walther and Rainer Metzger, Van Gogh: the Complete Paintings (2016)

A beautifully written piece about Van Gogh. It made me realise that I don't know enough about him.