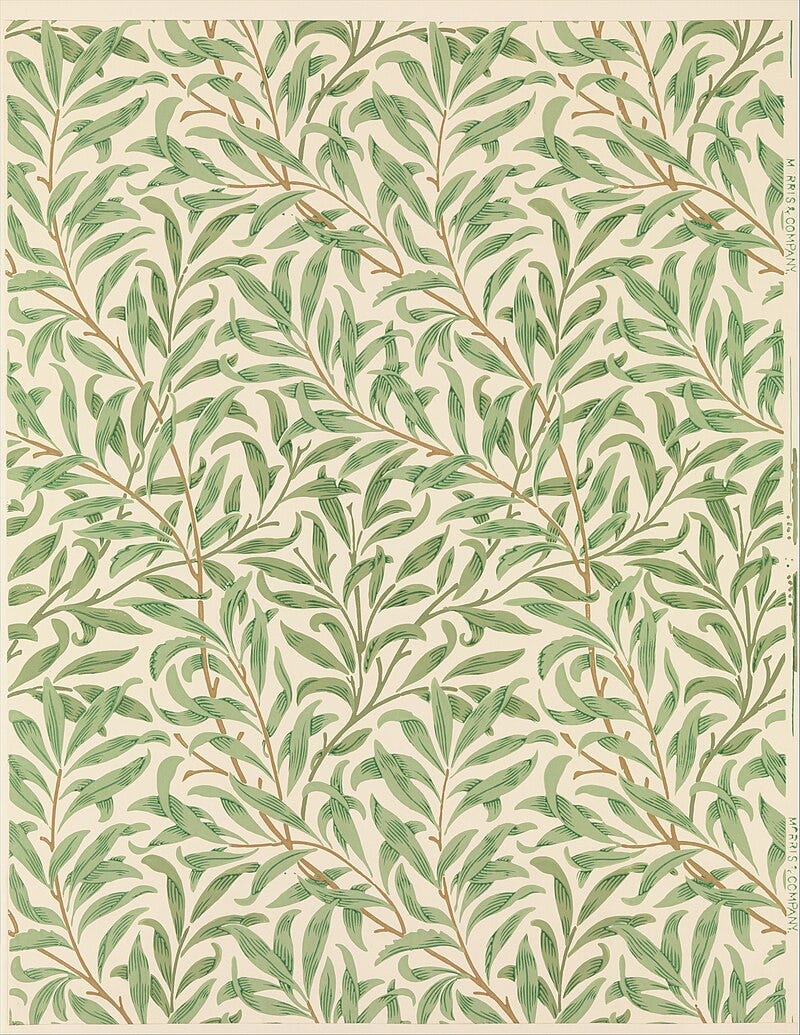

I get a happy, fuzzy, dopamine-y feeling from a good pattern. I am really drawn to flowy, floral type patterns, with lots of tendrils and swirls; I went to the recent William Morris wallpaper exhibition at my local art gallery in York three times, and each time it was like a warm bath for my brain. I find the curves, the rhythms, of a floral pattern deeply soothing. I enjoy ditsy prints, with lots of little flowers spaced out, but I find intertwined, wriggly patterns even nicer. My partner and I have just ordered the William Morris willow bough wallpaper for our house and I am so excited to turn our hallway into a dense foliate maze. Balm for my eyes. When we rented our flat, which had plain white walls that we weren’t allowed to drill into, I used masking tape to stick up sheets of posh wrapping paper with block prints and Chinoiserie-style wallpaper designs. When I’m stressed or trying to concentrate, I find myself doodling long, loopy, flowy lines down the margins of my notebooks.

Patterns make me happy - they give me a boost, and interestingly, I don’t fully know why. I am fascinated by why I love them so much. I grew up in quite a neutral house, so perhaps some of it is just rebellion from being around a lot of plain beige as a child. But I also think I am just being very human, in that a love for adornment and pattern is a deeply human trait.

The urge to create, wear and surround ourselves with pattern transcends temporal and cultural boundaries. Pattern-making is one of the most ancient forms of artistic production. The oldest known drawing in the world is a pattern, an abstract criss-cross design made using an ochre pigment, discovered in the Blombos Cave in South Africa and dated to an astonishing 73,000 years ago.

Western art history since the Renaissance has been obsessed with the figurative: the body in space, but so many cultures outside Europe have been much more concerned with pattern-making than creating paintings that look like little stage-sets. Islamic art is perhaps the archetype of this: in a religious culture that has historically rejected the portrayal of people, the artistic focus is instead on creating exquisitely rich patterns.

In January I went to the ‘Great Mughals’ exhibition at the V&A which showcased the arts produced during the ‘Golden Age’ of the Mughal Empire (around 1560 - 1660). The pattern-making on show was extraordinary and deeply immersive - intricate flowers, elegantly curved archways, looping calligraphy, dancing animals. After the exhibition, me and my friends pottered round the shops in Chelsea and had fun looking at the fabrics and wallpapers in one of the high-end interior showrooms. It really struck me how in a completely different social, religious and temporal context, here it was again: the human urge to decorate and adorn. My camera roll from that day out in London blends happily from Mughal carpets to modern-day luxury wallpaper. It was a joyfully pattern-soaked day.

The anthropologist Alfred Gell (1945 - 1997) had some ideas about pattern that I first encountered attending a lecture series on Islamic art as a student. I find myself thinking about Gell when I’m looking at a tapestry in a museum, or a floral dress I might buy. He argued that pattern possesses ‘tackiness’ (as in ‘stickiness’): ‘the essential property of surface decoration [is] its cognitive resistance, the fact that once one submits to the allure of pattern, one is liable to become hooked, or stuck, in it.’1

For Gell, the psychological power of pattern is its inherently unfinished property: patterns ‘slow perception down, or even halt it, so that the decorated object is never fully possessed at all, but is always in the process of being possessed.’2 In other words, there is always an imbalance, a lack of complete harmony, between the object and viewer, which keeps the two in a constant dialogue. The pattern can never be ‘solved’ or ‘finished’: it possesses an allure that demands constant re-visits. In this way, it destabilises the authority of you, the viewer, and gives the object power over you. It’s like a song you can’t get out of your head.

There can be something meditative and regulating about this loss of visual control. Allowing yourself to get lost in a pattern was an important aspect of art-viewing in the early medieval period. Perhaps no object better encapsulates this than the Book of Kells. This extraordinary manuscript, created in around 800 AD in either Ireland or Scotland, is composed of the four Gospel texts, and is adorned with elaborate, wriggling, eye-popping ornamentation. Interlaced forms that appear to be abstract are, upon closer inspection, revealed to be the squirming bodies of serpents, birds and monsters. There are cats and mice hidden among the tendrils of coloured ink, and even an otter diving to catch a fish. Simple shapes contain multitudes: microcosmic entanglements that dance and play within the boundaries of the letter-forms.

These mind-bending patterns help provide a pathway through the density of the text, guiding the eye through their stimulation, like streetlamps lighting up the road ahead. Without chapters or verses, the priest reading the text would instead have to rely upon braided motifs and hidden animal heads to guide his eye, and to help him mark out the key points in the stories being told. In searching out for the hidden details, the motion of the eye is slowed, and the mind focuses in to the tiniest of forms. This act of ‘zooming in’, done mindfully, adds extra gravitas to the content of the words. The reader is encouraged to slow their reading, perhaps also their breathing, to appreciate the sanctity of the words proclaimed in the text.

The urge to adorn the world with pattern and the pleasure of experiencing it has a long and thorny history of theoretical enquiry. The 19th-century art critic John Ruskin saw pattern and ornament as possessing a high moralistic virtue. Railing against the mass-production of the new industrial age, Ruskin saw beautifully patterned, handcrafted objects as markers of the artist’s love and care for their craft, and the pleasure of their work. A generation later, the architect and theorist Adolf Loos (1870 - 1933) published an aesthetic manifesto under the dramatic name Ornament and Crime, in which he made the highly questionable statement: ‘the evolution of culture is synonymous with the removal of ornamentation from objects of everyday use’. For Loos, pattern was emblematic of ‘primitive’ vulgar excess, to be bulldozed under the minimalist machine of modernity.

Although most of us would profess to disagree with Adolf Loos’ statement that ornament is an indication of cultural inferiority, we do live in a culture that frequently sees minimal neutrals as socially prestigious. Patternless ‘neutrals’ (white, beige, black) whether in the form of interior design or fashion, carries connotations of wealth and success. It’s clean, it’s sleek, its unemotional. It’s effortless yet also curated. There’s a certain kind of aspirational lifestyle floating around on the Internet that does not seem to include any kind of pattern at all. No bold prints, no ditsy florals, no Hawaiian palm trees and no animal print, no polka dots, no paisley, no plaid. I suppose it’s easier for things to look perfect without pattern - there’s no danger of visual disturbance, no aesthetic noise. It’s better to be silent than risk being out of tune.

In the Design Museum in Copenhagen, which I visited back in March, I was delighted to find a section dedicated to pattern with a beautifully written interpretation sign. It reads “Patterns resonate directly with the body through rhythm and repetition…patterns have the capacity to unite people across cultures, style periods, age groups and social classes”. The Museum makes the case for pattern as a democratising force, as it requires no prior knowledge to enjoy and appreciate. It links us to the rhythms of our own bodies, in our breathe and heartbeat, and the rhythms within nature. There is an argument to be made that stripping pattern away from our lives is to lose out on a ancient shared human tradition, that links us to our bodies and to each other, across time.

Perhaps this is why people are consistently drawn to make, wear and appreciate patterns across time: patterns link us with the most fundamental life-giving mechanisms within our bodies, and the natural world around us, with its temporal rhythms, and its multitude of harmonising shapes and forms. I wrote here about Leonardo da Vinci’s connection between the blood in human veins and water moving through a landscape: he was acutely aware of how the patterns in our bodies are mirrored in the geographical forces around us.

From the delicate branching of crystals to the whorls of ammonites and the intricate structures of honeycomb, patterns are embedded within the natural world. You don’t need to look much further than cutting open a red cabbage, or seeing a spider’s web. Perhaps pattern-making and pattern-viewing scratches a very human itch - to be connected to our bodies, whilst also being a part of something much bigger. To be grounded within our own physicality, whilst being deeply entangled with the world around us.

Image credits:

William Morris Willow Bough - Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Morris_wallpaper_designs#/media/File:Willow_Bough_MET_DP306734.jpg

Blombos cave art - Don’s Maps, https://www.donsmaps.com/blombos.html

Mughal carpet and wallpaper - my own photos

Lindisfarne Gospels - Chronicle/Alamy, via the Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2022/sep/14/the-lindisfarne-gospels-review-was-eadfrith-the-monk-britains-first-great-artist

https://smarthistory.org/the-lindisfarne-gospels/

Molly Mae’s house https://www.capitalfm.com/news/celebrity/molly-mae-house-boyfriend-tommy-fury/

Kourtney Kardashian’s house https://www.architecturaldigest.in/content/hollywood-celebrity-inside-kourtney-kardashian-home/

Design Museum display - my own photo

red cabbage - Getty Images/iStockphoto, copyright: RobertSchneider https://www.istockphoto.com/photos/red-cabbage-close-up

ammonite - Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ammonoidea#/media/File:Pleuroceras_solare,_Little_Switzerland,_Bavaria,_Germany.jpg

Alfred Gell, Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993), 82.

Ibid., 81

Wonderful topic, wonderful article! This is the first one I've read by you, and I look forward to discovering more :) Thank you!

I loved this Cathy, it was such an inspiring and informative read. You are absolutely speaking my language, I LOVE pattern. I worked for an Italian textile company for a long time and the patterns from their traditional damasks etc to more contemporary motifs were so beautiful. I was lucky to be able to explore their archive in Venice filled with fragments of antique fabrics, a true joy! And yes to the full body/mind experience of being immersed in pattern, the patterns found in the living world blow my mind, it makes sense to be drawn to them in our homes too xx